As global demand for clean energy and high-energy batteries surges, scientists are racing to develop more efficient and eco-friendly energy storage solutions. Compared to widely used lithium-ion batteries, sodium-ion batteries stand out due to their abundant sodium resources and lower costs. A crucial factor in enhancing their performance lies in identifying high-performance cathode materials. Scientists have long considered O3-type oxide cathodes (or O3-phase cathodes), which offer exceptional theoretical energy storage capacity because of their anion-redox activity (OAR). However, synthesizing these materials has proven challenging—previous attempts often produced impure products with disappointing performance, and the reaction process remained poorly understood.

Recently, a team led by Assistant Professor Xu Chao from the School of Physical Science and Technology (SPST) at ShanghaiTech has solved the tough challenge of synthesizing O3-phase sodium-ion battery cathode materials. This work sheds light on complex reaction mechanisms and paves the way for designing next-generation battery materials.

The synthesis puzzle: oxygen levels hold the key

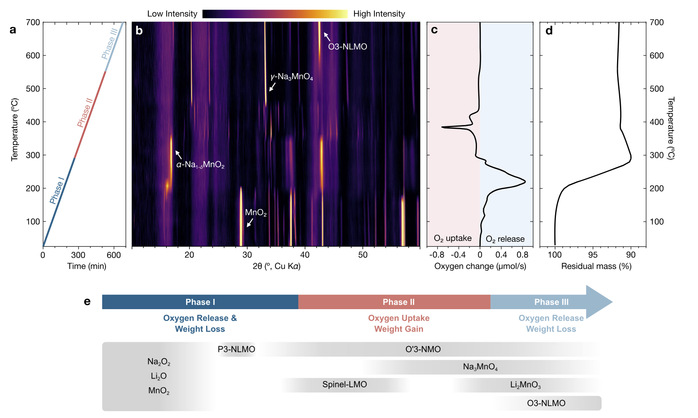

Xu’s team pinpointed the crux of the issue: the “atmosphere”—specifically, the oxygen concentration during synthesis. Past efforts using pure oxygen or inert gases like argon consistently failed. Through experiments with O3-Na[Li1/3Mn2/3]O2—a compound of sodium, lithium, and manganese—they employed cutting-edge real-time monitoring techniques, including X-ray diffraction, thermogravimetry analysis, and gas chromatography, to track changes in both the solid material and surrounding gases (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Real-time monitoring of O3-Na[Li1/3Mn2/3]O2synthesis.

Their findings uncovered a three-stage process: first, a significant release of oxygen lowers manganese’s oxidation state; next, oxygen absorption is necessary to “recharge” manganese to its optimal state; finally, excessive oxygen must be avoided to prevent the formation of high-oxidation-state impurities. Only a finely balanced low-oxygen environment (1-2% oxygen) yielded a pure O3-type cathode. This dynamic cycle of oxygen uptake and release, along with the formation of various intermediate phases, emphasized the complexity of the reaction.

Why oxygen matters

Simply put, oxygen levels guide the reaction’s course—similar to adjusting the heat when baking a cake. Insufficient oxygen prevents manganese from oxidizing adequately, resulting in low-performance byproducts; excessive oxygen leads to “overcooking,” which creates unwanted impurities. By comparing sodium-manganese-oxygen and lithium-manganese-oxygen systems, the team discovered that introducing both sodium and lithium complicates the reaction, highlighting the crucial role of oxygen.

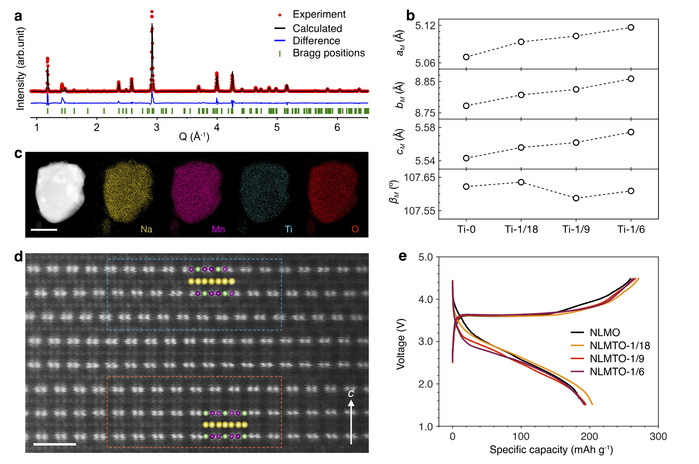

Armed with this insight, they developed a “dynamic controlled atmosphere” (DCA) strategy: supplying just the right amount of oxygen initially, then transitioning to an inert environment later. This approach not only produced pure O3-Na[Li1/3Mn2/3]O2 but also facilitated the creation of titanium-doped variants, NaLi1/3Mn2/3-xTixO₂ (x=1/18, 1/9, 1/6), with capacities exceeding 190 mAh/g and excellent reversibility (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Structure and electrochemical performance of titanium-doped NaLi1/3Mn2/3-xTixO₂.

From lab to life

This advancement doesn’t just solve the O3-type cathode synthesis puzzle. It’s the first to systematically unravel its intricate mechanisms, offering a roadmap for designing high-performance energy storage materials. “Our work is like finding a key to unlock the potential of high-capacity sodium-ion batteries,” said Xu. The team believes this progress will propel sodium-ion batteries into applications such as electric vehicles and renewable energy storage, enhancing sustainable energy solutions.

This study is published in the journal Nature Communications, titled “Enabling the synthesis of O3-type sodium anion-redox cathodes via atmosphere modulation.”

Three students from SPST—third-year PhD student Qiu Yixiao, second-year master’s student Liu Qinzhe, and fourth-year master’s student Tao Jiangwei—are the co-first authors. Prof. Xu Chao is one of the corresponding authors, and ShanghaiTech is the primary affiliation.